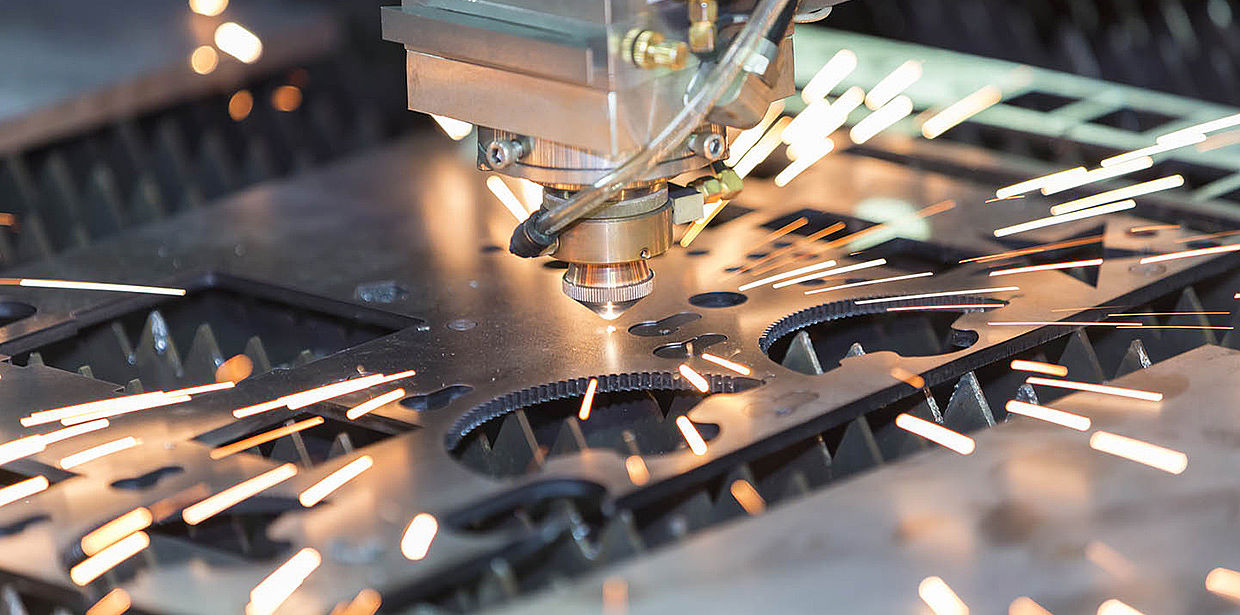

Laser cutting has become well established in sheet metal processing, especially for thinner materials. The reason: In contrast to punching or shear cutting, the laser is exceptionally flexible as a tool. This means that laser cutting is often worthwhile from batch size 1. Many job stores have specialized in this process, because it allows them to produce new workpieces for their various customers in an uncomplicated manner.

Special light enables laser cutting

Laser (composed of the words "light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation") refers to both the beam and the device used to generate laser beams. The laser beam used for cutting is therefore an electromagnetic wave. These waves differ from ordinary light by several factors: high intensity, often very narrow frequency range (monochromatic light), sharp bundling of the beam and great coherence (the waves have a fixed phase relationship in spatial and temporal propagation). A laser beam can heat and ablate almost any material, which in physics is called ablation.

Lasers are often named according to the properties of their optical laser medium, i.e. the material that generates the laser light. Important for sheet metal processing are above all the CO2 laser with gaseous laser medium and the fiber laser, which works with glass fibers.

Laser cutting consists of two operations

Strictly speaking, two processes take place simultaneously during laser cutting: First, the material at the cutting front absorbs the laser beam and heats up. Second, the blowing gas blows the ablated material out of the kerf and thus also protects the focusing optics from vapors and spatter.

Depending on whether the material is removed from the kerf as a liquid, oxidation product or vapor, a distinction is made between laser beam fusion cutting, laser beam flame cutting and laser beam sublimation cutting.

Laser cutting can also make deburring necessary

This also has consequences for the formation of burrs. It is true that laser parts made of mild steel and stainless steel can actually turn out burr-free, depending on the thickness and complexity of the contour. For this, however, the focusing optics and process parameters must be optimally set. The thicker the parts, however, the greater the fusion loss. Narrow contours can also make reworking necessary. Burr formation is unavoidable in aluminum parts cut by laser.

In the case of flatbed lasers, adhesions also occur on the underside of the sheet due to reflections from the support grid. This cannot be prevented even if all parameters are perfectly matched. In the case of laser flame cutting, the cut edges also have an oxide layer after the process, which must be removed.

Laser cutting works with steel up to a plate thickness of about 40 mm, with stainless steel up to about 50 mm and with aluminum up to 25 mm. Aluminum, however, is a difficult material to cut because it reflects most of the laser radiation and because its high thermal conductivity dissipates a lot of energy from the cutting gap. The same applies to copper.